- Thu. Apr 25th, 2024

Latest Post

Meet Luke Suess: Discover More about His News, Sports, and Job Endeavors

Luke Suess played a vital role in New Ulm baseball’s successful sweep of Worthington in their recent games. He showcased his skills by collecting three hits, driving in four runs,…

“Schmitz ready to resume operations at Van Hool on Monday” (Lier)

ACLVB has stated that the first employees are anticipated to return to work on Monday. The revival of the trailer division at Van Hool is scheduled to occur gradually. Specific…

The role of cutting-edge technology in enhancing Miami Township investigations

In Miami Township, Ohio, police are utilizing drones to enhance community safety and support officers. Chief Mike Mills stated that the department has only been using drones for about six…

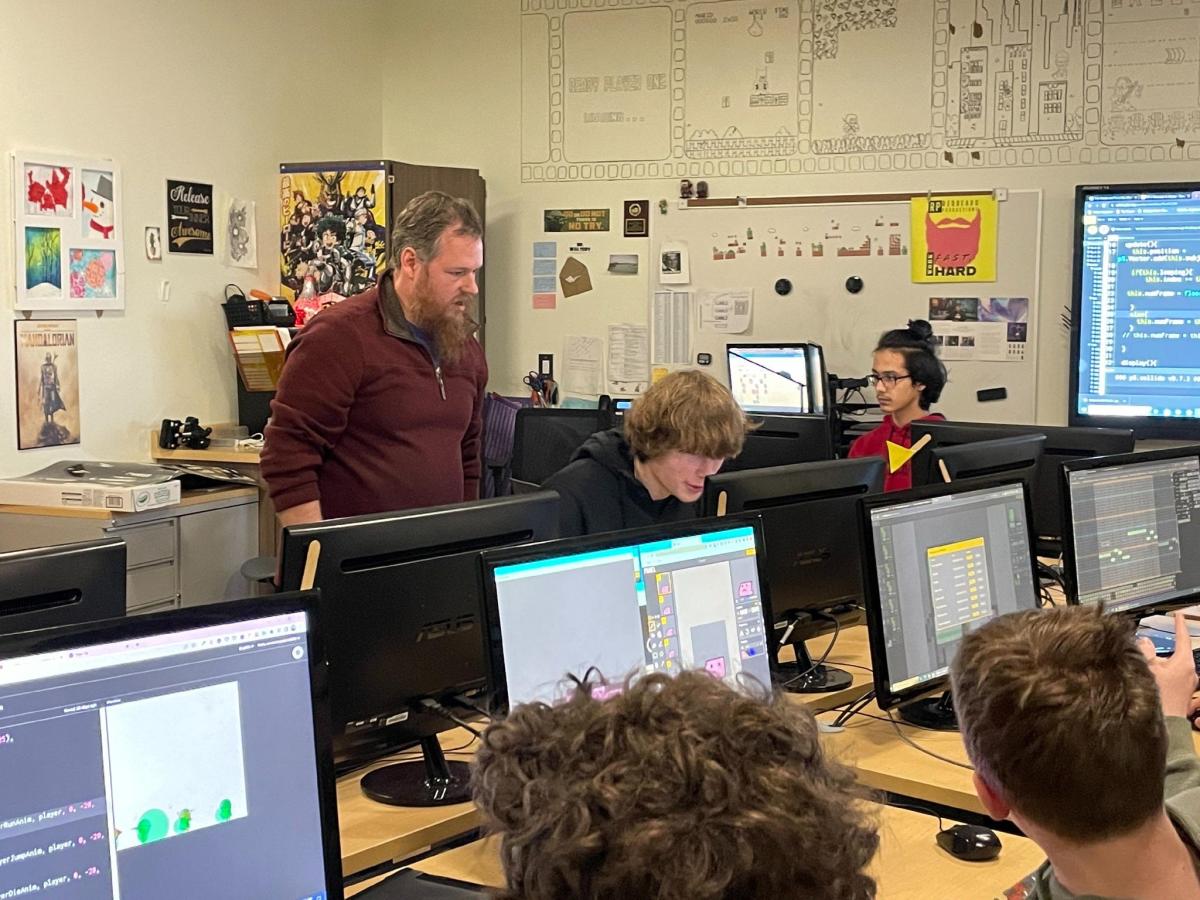

State Program Provides On-the-Job Technology Training for Licking Heights Students

Licking Heights Local Schools has partnered with the Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation to offer a High School Tech Internship program to 10 high school students. This program provides students…

Accountants are optimistic about the global economy in 2024

A new study by ACCA and IMA has found that finance professionals are feeling optimistic about the global economy. The Global Economic Conditions Survey (GECS) shows a rise in confidence,…

LG’s TV business bounces back to profitability thanks to increased demand in Europe and the rise of streaming services

In the first quarter, LG Electronics’ TV business returned to profitability due to the recovery of demand in Europe and the increasing popularity of streaming services. The South Korean electronic…

As Economic Growth Slows, Germans Consider Longer Work Hours and Delayed Retirement

German politicians and business leaders are addressing a controversial topic that was once considered taboo: the issue of German workers not putting in enough hours. The country’s weak economy has…

Two separate lifeforms unite for the first time in one billion years

Sign up for our Voices Dispatches email for a full digest of all the best opinions of the week. Stay informed with our free weekly Voices newsletter. For the first…

Meet Kiah Helget: Latest Updates on News, Sports, and Jobs

New Ulm Cathedral senior Kiah Helget had a standout performance in a recent softball game against Nicollet at Harman Park. Her two-run home run sealed the deal for the Greyhounds,…

FBI Investigates Video Released by Hamas Featuring Hirsch Goldberg-Paulin

Hirsch Goldberg-Polin, an individual who holds both Israeli and American citizenship, was kidnapped by Hamas militants on Black Saturday on October 7. According to reports from the Kan-11 television channel,…